Explain KZG - Moon math to scale Ethereum

What the f*ck is Zero Knowledge Proofs. For new people, who first time read about it, it’s a bit hard to understand, due to the mathematical complexity. They are referred to as “moon math” because they are so complex that they seem to be from another planet.

In this blog, I want to demystify the inner workings of Zero Knowledge Proofs and how they can be used to scale Ethereum.

This blog doesn’t make them any less complex, but I hope it makes them more understandable.

Introduction

In this post, I give an introduction to a critical ingredient to many zero knowledge proof systems: polynomial commitments. (I have another post about zkSNARKs, check it out here). I then briefly explain KZG, a specific polynomial commitment scheme in practice. I continue by discussing how KZG can be used to scale Ethereum by Ethereum’s Proto-Danksharding.

What is polynomial?

Polynomial is powerful math, and it’s used in many areas of mathematics, science, and engineering. A polynomial is a mathematical expression consisting of variables and coefficients. Polynomial can be used to represent large objects in efficient ways.

One standard objects that can be represented by a polynomial is an $n$-dimensional vector ($v\in \mathbb {F}_p^n$). We can craft a polynomial $\phi(x)$ to represent $v$ by ensuring that $\phi(i) = v_i$ for $i = 0, 1, 2, \dots, n-1$.

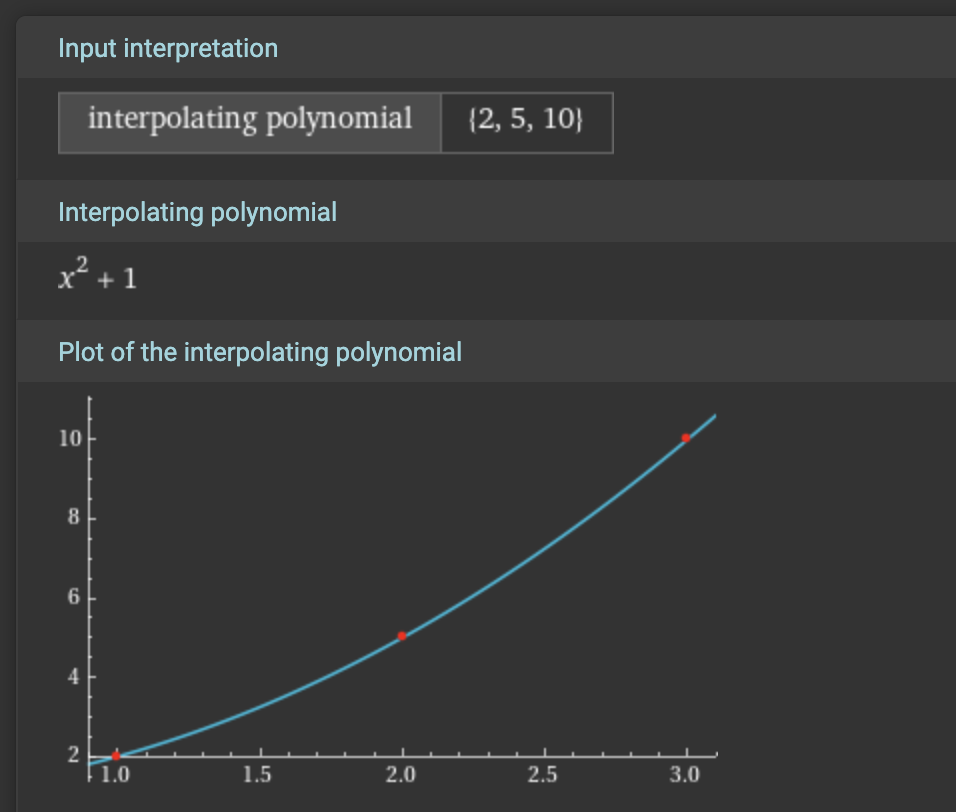

For example, we could take the 3-dimensional vector $v = (2, 5, 10)$ and represent it with the polynomial $\phi(x) = x^2 + 1$. You can plug in $\phi(1) = 2$, $\phi(2) = 5$, and $\phi(3) = 10$ to verify that this polynomial indeed represents the vector $v$. In this way, the polynomial $\phi(x)$ is a succinct representation of the vector $v$.

In general, we can represent any $n$-dimensional vector with a polynomial of degree $n-1$ which pass through all of them. This process is called polynomial interpolation.

What is polynomial commitment?

A polynomial commitment scheme is a commitment scheme, the committer can commit to a polynomial $\phi(x)$. The polynomial commitment scheme satisfy the following property: the committer should able to open certain evaluations of the polynomial $\phi(x)$ at any point $x$ without revealing the polynomial itself.

For example, the committer can commit to a polynomial $\phi(x)$ and later prove that $\phi(a) = b$ without revealing the polynomial $\phi(x)$.

Why we need polynomial commitment?

This is an awesome feature because it allows us to prove statements about the polynomial without revealing the polynomial itself. This is the core idea behind many zero knowledge proof systems. We can use it to prove that we have some polynomial that satisfies certain points ($a,b$) without revealing what the polynomial is.

Another reason what the polynomial commitment is useful is that the commitment $c$ is generally much smaller than the polynomial $\phi(x)$ itself. We’ll see a commitment scheme where a polynomial of arbitrarily large degree can be represented by its commitment as a single group element. Think about posting data to on-chain, where block space is a valuable resource and any sort of compression can be immediately translated into cost savings.

The KGZ polynomial commitment scheme

Now, moving to the KZG polynomial commitment scheme. KZG stands for Kate, Zaverucha, and Goldfeder, the authors of the paper that introduced the scheme. The KZG scheme is a polynomial commitment scheme that allows for succinct commitments to polynomials. KZG is widely used for many tasks in the blockchains spaces (e.g EIP-4844 - I will work through this later in this blog).

This section will briefly explain the math behind the KZG scheme. It’s not mean to be a comprehensive explanation, but rather a high-level overview.

Anyway, let’s dive into the math. The KZG polynomial commitment scheme consists of four steps:

1. Setup: The first step is a one-time trusted setup. Once the setup is done, it can be used to commit to many polynomials.

- Let $g$ be a generator of some pairing-friendly elliptic curve group $G$.

- Let $l$ be the maximum degree of the polynomial we want to commit to.

- Pick some random field elements $s \in \mathbb{F}_p$.

- Compute $\left( g, g^s, g^{s^2}, \dots, g^{s^l} \right)$ and publish it.

- Note that $s$ should not be revealed, it is a secret parameter of the setup, and should be destroyed after the setup such that nobody can figure out what $s$ is. Read more on Vitalik’s blog.

2. Commit: Commit to a polynomial $\phi(x)$

- Given a polynomial $\phi(x) = \sum_{i=0}^{l}\phi_i x^i$

- Compute the commitment $c = g^{\phi(s)}$

- By the way, The committer cannot compute $g^{\phi(s)}$ directly because he doesn’t know $s$ but he can compute it via the output of the setup: ($g, g^s, g^{s^2}, \dots, g^{s^l}$).

$\prod_{i=0}^{l} \left( g^{s^i} \right)^{\phi_i} = g^{\sum_{i=0}^{l} \phi_i s^i} = g^{\phi(s)}$

3. Prove: We really have commitment $c = g^{\phi(s)}$ and want to prove that $\phi(a) = b$.

- Compute proofs

$\pi = g^{q(s)}$, where $q(x) := \frac{\phi(x) - b}{x -a}$

This is called the quotient polynomial. Note that $q(x)$ exists if and only if $\phi(a) = b$. The existence of this quotient polynomial therefore serves as a proof of the evaluation because The polynomial remainder theorem.

4. Verify: Verify the proof $\pi$.

- Verify that:

$e\left( \frac{c}{g^b}, g \right) = e\left( \pi, \frac{g^s}{g^a} \right)$, where $e$ is a non-trivial bilinear mapping.

To proof this equation, we can use the bilinear pairing properties:

$e\left( \frac{c}{g^b}, g \right) = e\left( \pi, \frac{g^s}{g^a} \right) \iff$

$e\left( g^{\phi(s) - b}, g \right) = e\left( g^{q(s)}, g^{s - a} \right) \iff$

$e\left( g, g \right)^{\phi(s) - b} = e\left( g, g \right) ^{q(s)(s - a)} \iff$

$\phi(s) - b = {q(s)(s - a)}$

Read more about pairing: Exploring Elliptic Curve Pairings

Note that: Evaluation proofs in KZG polynomial commitments leverage the polynomial remainder theorem.

Demm, I know it’s very hard to understand, but I hope you can get the idea behind the KZG polynomial commitment scheme.

Ethereum’s Proto-Danksharding

Ethereum’s Proto-Danksharding is a proposal to scale Ethereum by using polynomial commitments, which aims to make it cheaper for rollups to post data on Ethereum’s L1. However, the data will not be accessible from Ethereum’s execution layer, only a commitment to the data blob will be accessible from the execution layer.

Now, how Ethereum create commitment for to the data blob. The data blob is a large object, and it can be represented as a polynomial. Ethereum can use the KZG polynomial commitment scheme to commit to the data blob. The commitment to the data blob is a single group element, which is much smaller than the data blob itself and make it cheaper to post data on Ethereum’s L1.

One very useful feature which is enabled by polynomial commitments to data blobs is that of data availability sampling (DAS). With DAS, validators can verify the correctness and availability of a data blob without needing to download the entire data blob.